Several people have read the GDC slides, and asked for more info on the algorithms I used for the StarTopia "patch". The GDC slides were extremely brief, because the original proposition was to include a roundup of all the various lighting solutions and their pros and cons. And it's amazing how little you can cover in an hour-long lecture. So yes, they were very brief on the actual technique I developed here.

Another dirty little secret was that the algorithm wasn't quite tuned by the time I did the GDC talk, and in fact I later discovered it had one massive bug that meant it wasn't scaling SB resolution with camera distance! I'm amazed it worked as well as it did. Anyway, the theory was right, even if the code was a little borked and fudged when I actually presented the talk.

The basic idea is that each light has a bunch of shadowbuffers associated with it, and each shadowbuffer has a frustum that determines which direction it looks in and the size of its field-of-view in radians. In practice I store this frustum as a cone rather than a square or rectangular-based pyramid. It also has a "pixel density" which is measured in pixels per radians. The idea is that with the FOV angle, the position of the camera, light and object, and some sort of user "quality" metric, you can calculate the pixel density required, and therefore the size of texture that the SB needs to hit that quality metric. This sounds more complex than it is.

The essence of the algorithm is then very simple:

Of course, you don't actually create all these frustums, only to then merge them together - that would be expensive. But that is the concept to hold in your head. It should be obvious that as long as you can handle any single light/receiver interaction, this algorithm always works. In pathological cases, you can't do much merging, and you end up rendering a lot of frustums, but those cases very rarely happen. In practice, you do a lot of merging and very few shadowbuffers come out the end.

Note that this algorithm never asks about shadow casters when deciding which shadowbuffers to use for which objects, and how big they are going to be. All it asks about are receivers. Once the shadowbuffers are all sorted out, only then do we ask which objects need to be rendered into the SB to cast shadows. Each shadow caster may be rendered into multiple SBs, and it doesn't matter if the caster does not completely fit inside the SB.

This demonstrates a fundamental difference between shadowbuffer-based techniques and shadow-volume ones such as stencil shadows. Volume-based techniques mainly care about casters - once you have rendered the shadow volumes from all the casters for a particular light, then you can render any objects you like to receive the shadows. By contrast, shadowbuffer techniques concentrate on shadow receivers. Once you have decided which SBs are needed for which receivers and how to get the right texel densities efficiently, rendering the casters is easy - the size and type of the caster does not affect your decisions. This characteristic means that shadowbuffers work really really well for outdoors envionments where the camera mainly looks at a reasonably-sized patch of ground (think an RTS or something like Dungeon Siege). Even though there might be huge buildings and mountains casting shadows into the scene, the shadowbuffer textures are still only small, so the fillrate demands are small. By contrast, shadow-volume techniques basically mean that each mountain you have casting a shadow into the scene does several full-screen incs and decs of the stencil buffer. Ouch!

The code uses cones to approximate frustums, and does lots of intersections and unions of cones, and also generation of cones from bounding spheres. I couldn't find a library to do these, so I had to work them all out from scratch. It's not that hard, but my algebra is pretty rusty, so I found it painful. For those wishing to avoid all the strife, try this.

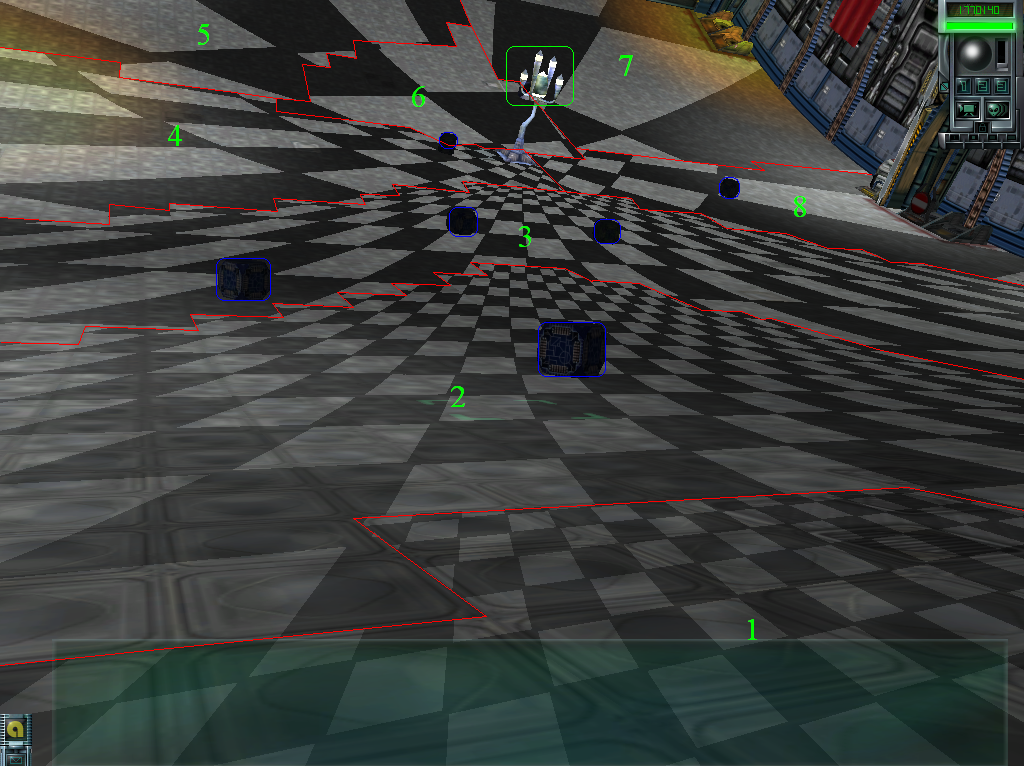

Here are some diagrams of the algorithm in action. This is a test scene with just one light, a lamp-post with an omnidirectional light at its top. It's sitting on the bare deck, with some dark blueish cubes added to try to show the different scales (the pattern of the deck is a regular square grid, but it is fairly subtle). Instead of rendering shadow-casters to the shadowbuffers, they have been filled with a chequerboard pattern a fixed number of texels in size to show the relative size of texels in each of the shadowbuffers. Texel size has been massively increased to make the effect easily visible. The perspective is slightly odd, because StarTopia is set inside a torus, so the deck curves upwards, but hopefully you can see what's going on.

The shadowbuffers, shown with chequerboard patterns. Note the moderately even distribution (within a factor of around 4) of texels in the scene. Also note the projections radiating from the omnidirectional light of the lamp-post. The blue/grey structure in the top/right of the scene is the wall of the station, showing the curvature of the deck. Walls are not shadowbuffered, since they were originally constructed as a single huge object, and so are too large to add to the shadowbuffering algorithm.

Same scene, with hand-drawn annotations. Red lines separate green-numbered shadowbuffers, blue boxes are cubes that are all the same physical size. The green box is the light.

Notice how in the vicinity of the light, multiple shadowbuffers (4-8) are used to keep the frustum FOV below 120 degrees, but they all have roughly similar texel densities. Closer to the viewer (1-3, and to some extent 4), you get the classic "duelling frustums" case, and multiple shadowbuffers are used to allocate texel density evenly to produce a consistent pixel/texel ratio. This balance between maximum FOV and evenly-distributed texels is not a pre-defined transition, it happens naturally as the camera, lights, and objects move around. It is possible that a more aggressive frustum-merger could get rid of SB 6 and grow SBs 5 and 7 to include its receiver tiles, but the current one is very fast and gets reasonable average-case results.

Even though this a simple 2D example with a scene composed entirely of uniform-sized floor tiles, the shadowbuffering engine does not know this - it treats everything as being an unstructured sea of arbitrary-sized 3D objects, so this balancing will work will any scene you wish to throw at it. StarTopia includes plenty of objects with odd sizes and shapes, including some very large rooms, and the algorithm copes very nicely with the complexity. And again, one of the advantages is that the artists do not need to worry much about the limits of the shadowing algorithm - in the case of StarTopia, they certainly didn't, as the game was published in 2000, four years before the shadowbuffering algorithm was added! No art has been changed to try to help the algorithm. The only places that do not currently work well are large objects with lights close to or inside them.

Some final results here.

Here is pseudocode that I've translated directly from the actual working code. There's a bunch of fairly standard optimisations that I've omitted for clarity, but this is the algorithm, and it works pretty well.

Get current camera data;

Make approximate viewcone for camera;

For each object

{

Find bsphere for object;

Find whether object is visible to camera using bsphere/cone intersection;

Make camera-space viewcone for object from bsphere;

Calculate the desired texels per meter using distance from camera and desired global "quality" metric;

}

For each light

{

For each object

{

Ignore objects that aren't affected by this light;

Add the ones that are affected to the light's object list;

Make a light-space viewcone for the object;

if the object is also visible to the camera

{

found=false;

// Try to find an existing shadowbuffer that encloses the object AND has a high enough density

for each existing shadowbuffer this light owns

{

if the object viewcone is enclosed by the shadowbuffer viewcone

{

texels per meter = SB->PixelDensity / object's distance from light;

if ( texels per meter >= object->desired texels per meter )

{

Add object to list of objects that use this SB;

Add SB to list of SBs that this object uses;

found=true;

}

}

}

if ( !found )

{

// None of the existing shadowbuffers is good enough

// Look for one we can grow slightly

// There are often a number of them, so try to find the best.

// Best = the one that ends up having the smallest base-cone angle.

best SB = none;

best cone angle = inf;

best pixel density = -1;

desired pixel density = obj->texels per meter * obj->distance from light;

for each existing shadowbuffer this light owns

{

Find the union between the SB's existing cone and the object's light-space cone;

// The arbitrary angle I use is 120 degrees - seems to work OK

if cone angle is above arbitrary cutoff angle, continue;

if cone angle is above best cone angle, continue;

new desired pixel density = max ( SB->pixel density, desired pixel density );

Find resulting texture size for cone angle and new desired pixel density;

if size is not too big

{

best SB = this one;

best cone angle = this cone angle;

best pixel density = new desired pixel density;

found = true;

}

}

if ( found )

{

Add object to list of objects that use best SB;

Add best SB to list of SBs that this object uses;

best SB->cone angle = best cone angle;

best SB->pixel density = best pixel density;

}

}

if ( !found )

{

// Still nothing acceptable! OK, just make a new SB then.

new SB->view cone = obj->light-space cone;

new SB->pixel density = obj->texels per meter * obj->distance from light;

Add object to list of objects that use this SB;

Add this SB to list of SBs that this object uses;

Add this SB to list of SBs that light uses;

}

}

}

for each SB that this light uses

{

Actually create the rendertarget texture for the SB;

if this fails, kill the SB;

}

// Find which objects cast shadows into the SBs.

for each object that this light affects

{

for each SB this light has

{

if obj->bsphere and SB->viewcone intersect

{

Add the object to the SB's caster list;

}

}

}

}

For each light

{

For each SB the light has

{

Change rendertarget to the SB's texture;

Clear buffer;

Calculate the SB's camera matrices;

Set up SB rendering;

Render list of casters into the SB;

}

}

Change rendertarget to the standard back buffer;

Calculate the standard camera's matrices;

Render all objects with appropriate lights and SBs;